«There are a hundred ways to serve the country….’ Based on these words of J. V. Foix, 1 Tàpies, spoke of the effectiveness of the artwork and placed the importance of artists alongside that of other activities, such as science, research, study, the practice and technique of manual work, medicine… “Everything vibrates and acquires meaning when there are great ideals rooted in our smallest actions, however individualistic they may seem; when the great virtues – hope above all – are our driving force. Everything is useful then, nothing is too petty. The love for our fellow men (…) permeates everything, even though we may not have the slightest vocation for politics”. 2 But ‘there are special conditions that force the poet to take the place of the politician. Besides the work, there can sometimes be an action, a political statement that also counts. (…) Ways of expression that, thanks to the investiture that the artist’s work exerts on the imagination of the people, in some cases it can be more powerful than any statement from a politician».3

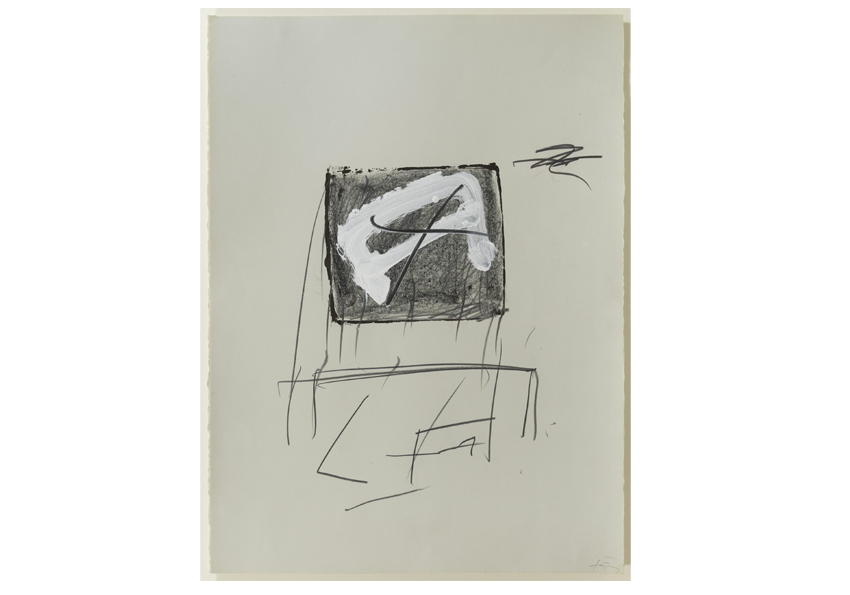

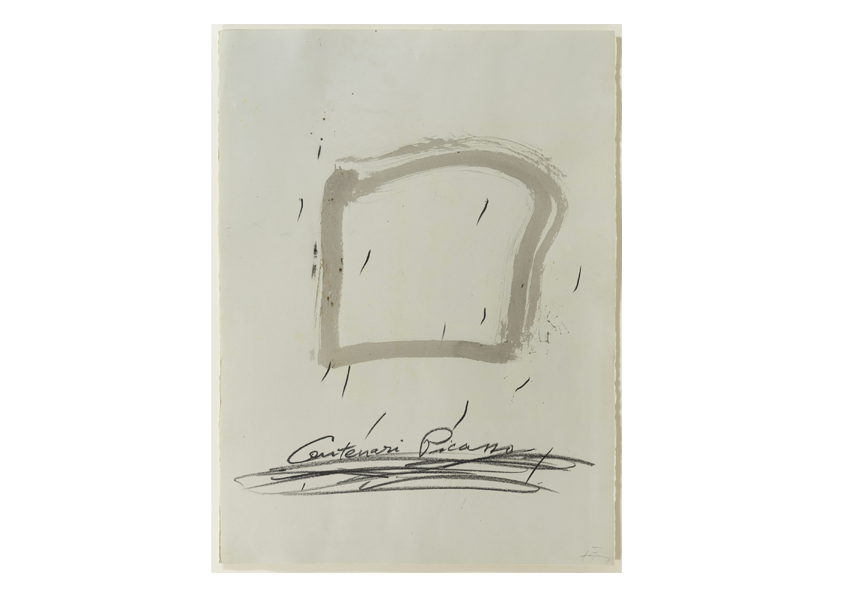

[Antoni Tàpies, Picasso 1881-1981, 1981. Poster made to commemorate the centenary of the birth of Pablo Picasso.]

One of these special conditions occurred in 1981, when Tàpies was commissioned by Barcelona City Council to dedicate a monument to Picasso as part of the commemoration of the centenary of his birth. The sculpture would be located on Passeig de Picasso, at the junction between the pedestrian area that connects Santa Maria del Mar, through the Born, with the Greenhouse of the Parc de la Ciutadella. Tàpies accepted the commission:

For my materials, I chose furniture that corresponded more or less to the era that Picasso fought against and that represented the comfort and conformism of that time, and I cut them through with iron beams, which symbolised anti-comfort. The resulting sculpture would be predicated on that phrase by Picasso that says that ‘painting is not made to decorate apartments. It’s an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy. 4

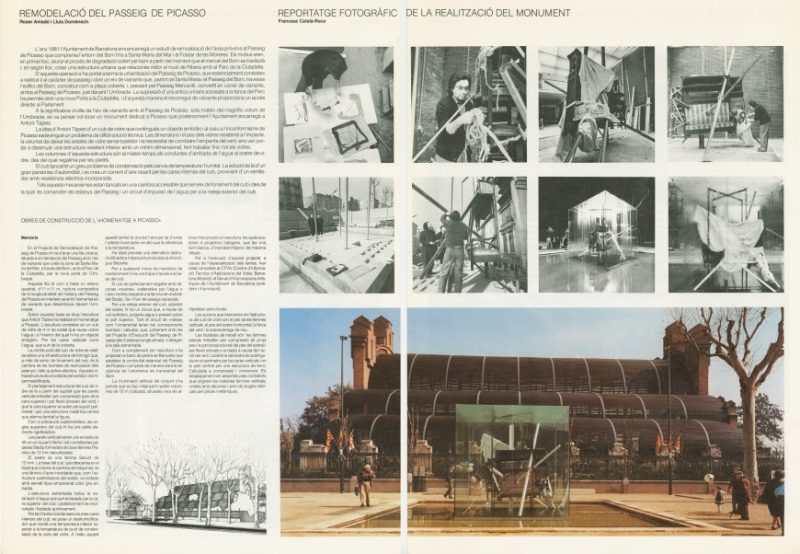

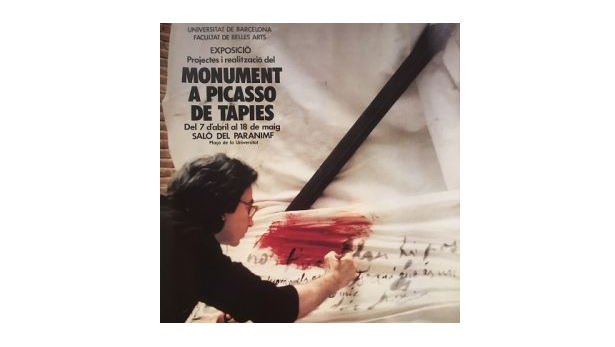

[Special issue of the newsletter of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the Universitat de Barcelona dedicated to the exhibition Projectes i realització del Monument a Picasso, de Tàpies (Projects and construction of the Monument to Picasso by Tàpies), presented at the Paraninfo Hall, Universitat de Barcelona, April-May 1983.] 5

Monument Homenatge a Picasso (Tribute to Picasso Monument) is an assemblage that juxtaposes several pieces of modernista furniture from the period when Picasso lived in Barcelona, with some elements and materials that allude to the industrial city of that time. Among the pieces of furniture, a bench seat with mirror and cabinet is cut through by white-painted iron beams forming an X. Next to it is a stack of three chairs tied together with ropes. White blankets spread from the top of the beams to cover the backs of the furniture, with a stain of red paint in the centre. As we approach, we discover graffiti written by Tàpies, reminiscent of some well-known statements by Picasso. Reinterpreted by Tàpies’ thought and gestures, these are not intended to be taken as literal quotations. “When I don’t have white I use red’ alludes to ‘When I don’t have blue I use red”, as recorded by Paul Éluard. 6 Adapting Picasso’s words, Tàpies warns us that the artist’s need to express himself sometimes goes beyond the means at his disposal. Then we find the best-known phrase: “No, painting is not made to decorate apartments. 7 It’s an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy”, an affirmation of the artist’s political commitment and a claim to the social dimension that art must have.

The sculpture is covered by a glass cube of four metres square, with water running down its vertical faces, and is located in the centre of a shallow pool of eleven metres square. The monument was inaugurated on 18 March 1983. 8

[Poster for the exhibition Projects and the realisation of the Monument to Picasso by Tàpies, presented at the Paraninfo Hall, Universitat de Barcelona, April-May 1983.]

In remembering Picasso, Tàpies brought back a period of time to Barcelona, his city. Based on a sculpture that is old and new at the same time – as Tàpies said of Picasso himself –, the artist embraces the confrontation that sees the end of one era and the advent of another. Tàpies exposes the complacency of the prosperous and bourgeois society of Barcelona at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, by contrasting and confronting it with the rebellious spirit of another society that had evolved, thanks to the non-conformism of those who were and continue to be politically committed. Picasso, said Tàpies, ‘was the end of an era. But at the same time 9 (…) he helped us glimpse, intuitively at least, a whole possible new world.». 10

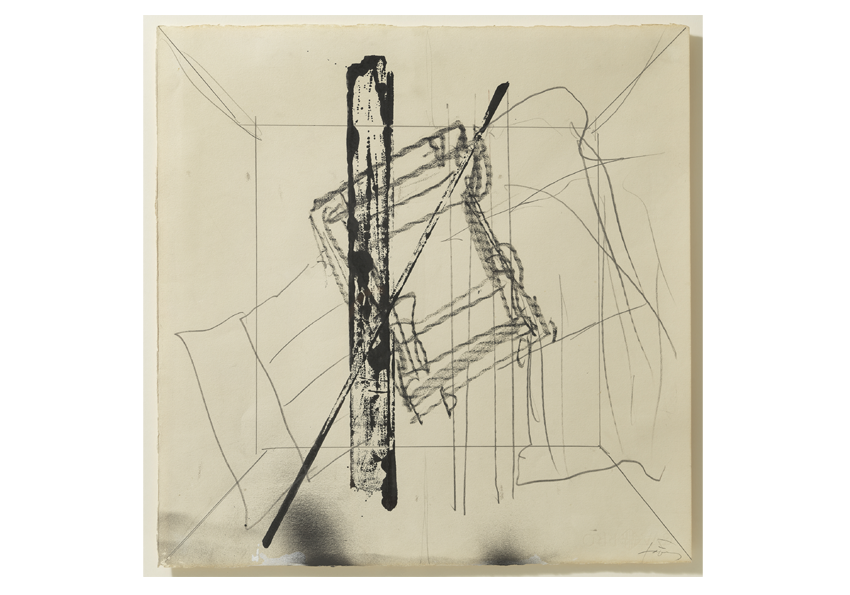

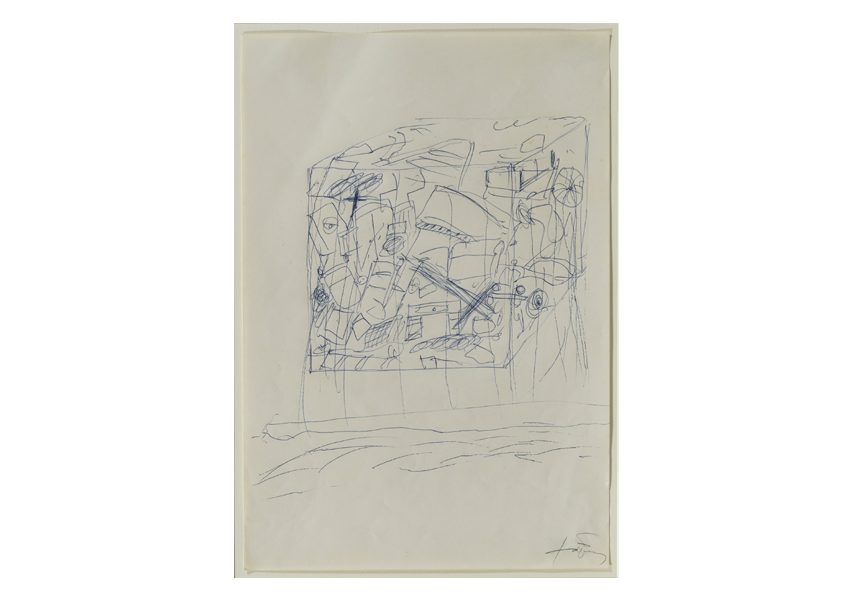

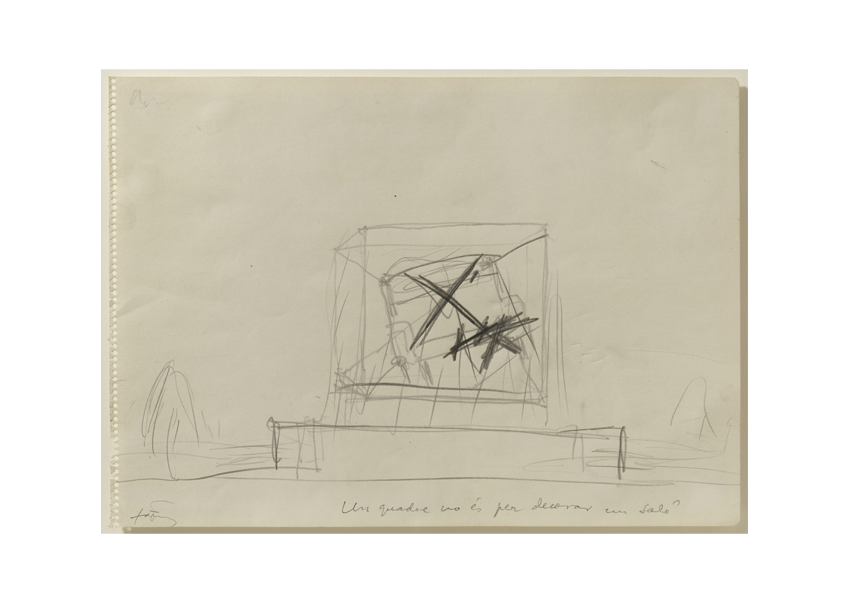

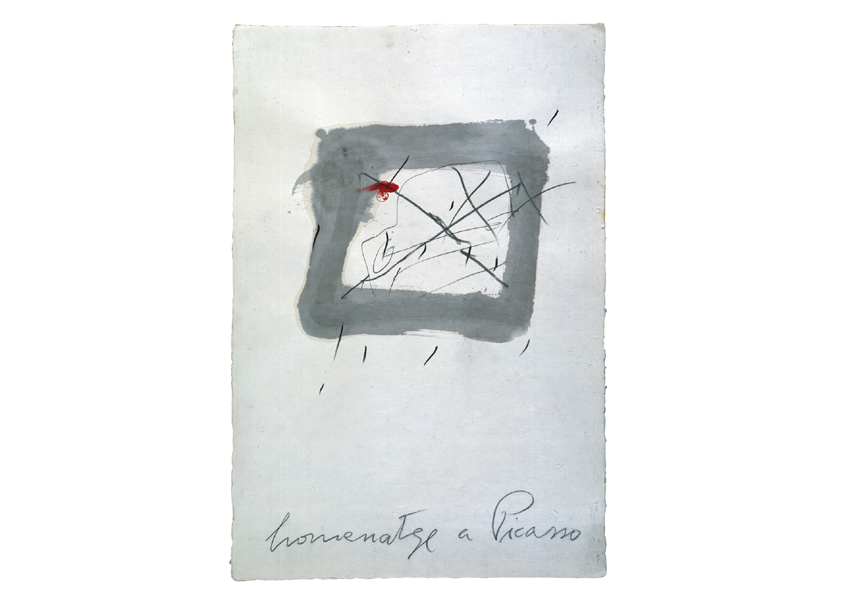

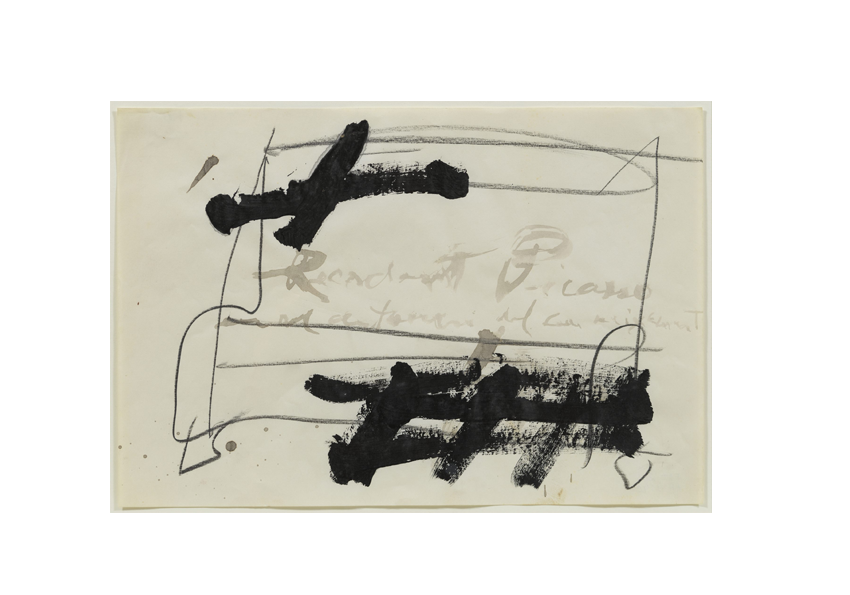

Of the fifteen preparatory drawings for the sculpture, twelve are part of the Fundació Antoni Tàpies Collection. 11 Observing them carefully, as well as being able to imagine the process of conception, we can comprehend the ideas that the sculpture expresses, such as the juxtaposition of planes and elements, the play between fullness and emptiness, stillness and movement, the crowding of objects, the presence of the furniture, the decision to cut through a piece of furniture and raise it at one end, the X that marks it, the red stain, the falling water, the word record (memory), and once again the quotation “Painting is not made to decorate a living room…” 12. In the drawings, however, all these ideas are treated in a more individualised way.

[Antoni Tàpies Homage to Picasso I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, IX, X, XII, XIV, XV, 1981. © Fundació Antoni Tàpies / VEGAP, 2023.]

In Picasso, as in other pioneering avant-garde artists, Tàpies recognised from a young age the importance of the fact that reality, and with it knowledge and ideas, could be expressed in new ways through modern art. In the 1940s, during the postwar period and in the midst of Francoism, when Tàpies was training as a painter, he studied the work of Picasso at a time when avant-garde art had no place in Catalonia or Spain, ‘a world as closed as the one in which we lived”. At that time, participating in these new forms was a political gesture in itself. “There had to be truths that were hidden from us and that needed to be rediscovered”. 15

Tàpies recognised Picasso’s disdain for academic and conservative art, based on classical forms of representation so admired by the Franco regime: “In him [Picasso] there was a real need to break with the type of reality represented until then by traditional painting, that is to say, the language that reproduces the images that our eyes give us, because he simply no longer believed in it.” He also admired his tireless search for the transformation of language, but also his ability to know first-hand “that the process of creating a way of saying, a style, can sometimes be a slow effort, not only of a lifetime, but of generations”. 16

Throughout his artistic career, Tàpies dedicated certain texts to Picasso and referred to him in various writings and interviews, recognising the importance of his artistic legacy, sometimes associating it with the image of the kaleidoscope: “…with his work he seemed to have taken all traditional painting to pieces and put it inside a kaleidoscope with which he kept giving us strange combinations”, “to get us closer to the new reality – irreproducible with the language of the eyes – that scientists were telling us about”, “twentieth century thinkers and poets 18 – M. Planck, W. Heisenberg, A. Einstein, N. Bohr, among others –, who “corroborated the old lesson that reality is not only what we see with our eyes’, ‘and that under the appearances of what is in space and time there is another, deeper, truer reality that has even transformed the idea we had of these two concepts”. 19

Tàpies also dedicated several works to Picasso, such as the series of twelve drawings A Picasso I-XII, which he made to commemorate the artist’s ninetieth birthday in 1971, a time when the ultra-right was attacking art galleries and bookstores in Barcelona and Madrid that were exhibiting works by Picasso as a birthday tribute”. 20

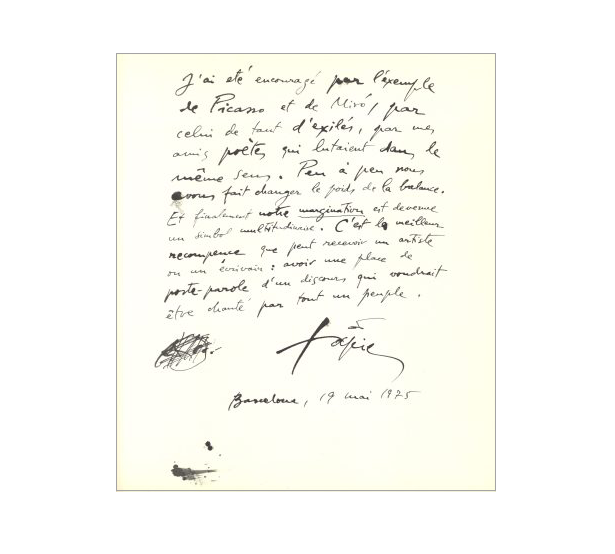

For Tàpies, Picasso and Miró were examples of modern and committed artists. In a manuscript from 1975, he expressed his gratitude to both artists, whom he always addressed as masters:

I was encouraged by the example of Picasso and Miró, by that of so many exiles, by my poet friends who fought for the same cause. Little by little we have altered the weight of the scale. And finally, our marginalisation has become a common symbol. It is the best reward for an artist or writer: to become the mouthpiece for a discourse that wants to be chanted by all the peoples. 21

[Text written as part of the commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of Picasso’s death and the sixtieth anniversary of the opening of the Museu Picasso in Barcelona, within the triple celebration Picasso, Tàpies, Miró (2023-25).]

With the public sculpture Monument Homenatge a Picasso, Tàpies recovered one of the first meanings of the word monument, from the Latin monumentum, derived from monere: to remember, to suggest, to warn. Keeping the memory alive, Tàpies keeps us alert, making clear, once again, the aspiration that art can have a social function. 22

Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, June 2023.

[Imagen de cabecera: Antoni Tàpies. Monument Homenatge a Picasso, 1983. Objeto-ensamblaje dentro un cubo de vidrio. 4 x 4 x 4 m. Colección Ajuntament de Barcelona, Barcelona.]

___

1 – Antoni Tàpies, ‘Avantguardisme i col·lectivitat’, L’art contra l’estètica. Barcelona: Ariel, 1974. First published in La Vanguardia, 9 May 1973.

2 – Ibid..

3 – Ibid.

4 – Antoni Tàpies, ‘Dibuixos preparatoris per al monument’, Projectes i realització del monument a Picasso de Tàpies. Newsletter of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the Universitat de Barcelona (Barcelona), April – May 1983.

5 – The newsletter contains: ‘Homenatge a Picasso’, Carles Camps and Xavier Franquesa; ‘Dibuixos preparatoris per al monument’, Antoni Tàpies; ‘Remodelació del Passeig de Picasso’, Roser Amadó and Lluís Domènech; ‘Reportatge fotogràfic de la realització del monument’, Francesc Català-Roca; ‘Sobre la idea de monument’, Josep Muntañola Thornberg; ‘Els dèficits monumentals de Barcelona’, Oriol Bohigas.

6 – Picasso said: ‘Quand je n’ai pas de bleu, je mets du rouge.’ Éluard, Paul, ‘Donner à voir’, ‘Peintres’, 1939, in Oeuvres complètes, I. Paris: Gallimard, 1997: p. 940.

7 – On the sculpture it says ‘apartments’; in the drawings, ‘living room’.

8 – That same year, from 7 April to 18 May, the exhibition Projectes i realització del Monument a Picasso de Tàpies took place in the Paraninfo Hall of the Universitat de Barcelona. A video was shown about its production and installation process with several interviews; the preparatory drawings; a photographic reportage by F. Català-Roca on the process of creation, realisation and installation; some works and assemblages by Antoni Tàpies (Porta metàl·lica i violí, 1956; Cadira i roba, 1970; Pila de plats, 1970; Taula, 1970; Palla coberta amb drap, 1971; i Armari, 1973); and sketches and plans by the architects Roser Amadó and Lluís Domènech, who directed the installation of the sculpture and the remodelling of the street.

9 – Antoni Tàpies ‘Picasso total. Nou i vell’, in L’art contra l’estètica. Barcelona: Ariel, 1974.

10 – Antoni Tàpies ‘El testimoniatge de Picasso’, in L’art contra l’estètica. Barcelona: Ariel, 1974. Article published in the children’s magazine Cavall Fort, no. 253 (June 1973).

11 – Antoni Tàpies, Homenatge a Picasso I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, IX, X, XII, XIV, XV, 1981. Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona. See the Collection online: www.fundaciotapies.org/la-colleccio/

12 – In the preparatory drawings it says ‘living room’ in the sculpture, ‘apartments’.

13 – Núria Homs, ‘Tàpies mira Picasso’, in Picasso a la retina. Artistes catalans retraten Picasso. Caldes d’Estrac: Fundació Palau, 2023 [in press].

14 – Antoni Tàpies, ‘Tres entrevistes. I’, in L’art contra l’estètica. Barcelona: Ariel, 1974. The text is based on the transcription that Lluís Permanyer made of the conversations he held with Antoni Tàpies for the articles published in La Vanguardia on 18 and 25 March and 1 and 8 April 1973.

15 – Ibid.

16 – Antoni Tàpies, ‘Picasso total. Nou i vell’, in L’art contra l’estètica. Barcelona: Ariel, 1974.

17 – Antoni Tàpies, ‘El testimoniatge de Picasso’, Op. cit.

18 – Antoni Tàpies, ‘Picasso total. L’heroi’, in L’art contra l’estètica. Barcelona: Ariel, 1974.

19 – Antoni Tàpies, ‘El testimoniatge de Picasso’, Op cit.

20 – Núria Homs. Op cit.

21 – Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, 19 May 1975. Manuscript published in Tàpies. Basel: Galerie Beyeler, 1975.

22 – Antoni Tàpies. «Dibuixos preparatoris per al monument». Op. cit.